History

Plastic Products Since 1936

Oy Plastex Ab is among the pioneers of Finnish plastics industry. It was one of the first entrepreneurs in the field half a century ago.

The story begins on July 7, 1936, when the Polish‑born engineer Igor Lawdansky founded a jewelry‑box and case factory in the basement at Snellmaninkatu 23 in Helsinki, producing buttons and other small items from Bakelite as well as electrical accessories.

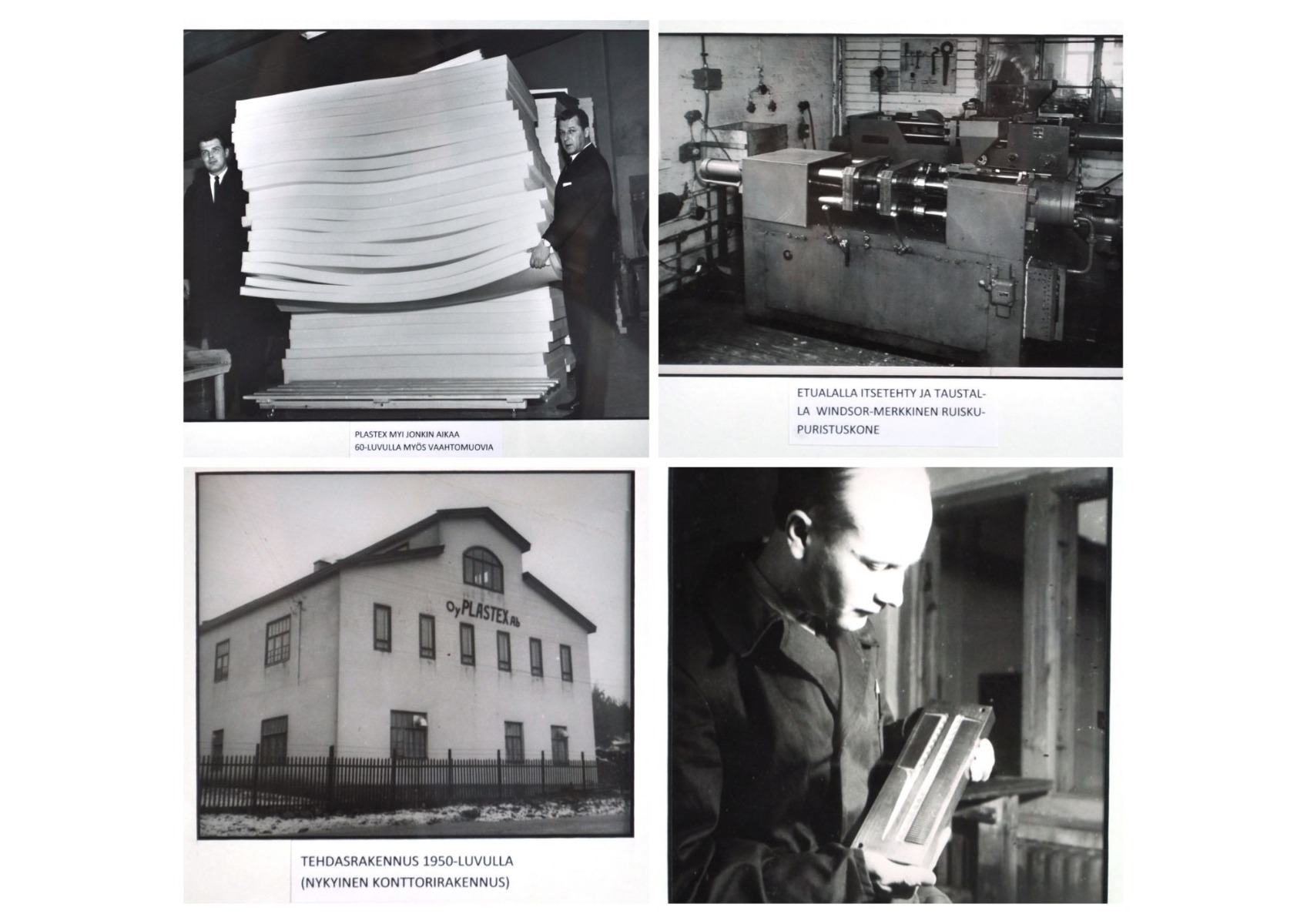

Production expanded, more space was needed, and it was found at Lohja station in a former kindling factory, to which an additional floor was built. In 1943 the name of the jewelry‑box and case factory was changed to Oy Plastex Ab, and around the same time the plant moved from Helsinki to the Lohja station area. The company’s offices are now in that first factory building.

The plant operated in Lohja for only a couple of years before death cut short Igor Lawdansky’s life’s work, and the company was inherited by his widow, Irja Lawdansky. She married Plastex’s sales representative, Olavi Tarkko. Leadership of the company passed to Tarkko in 1946.

Combs, Funnels, and Soap Boxes

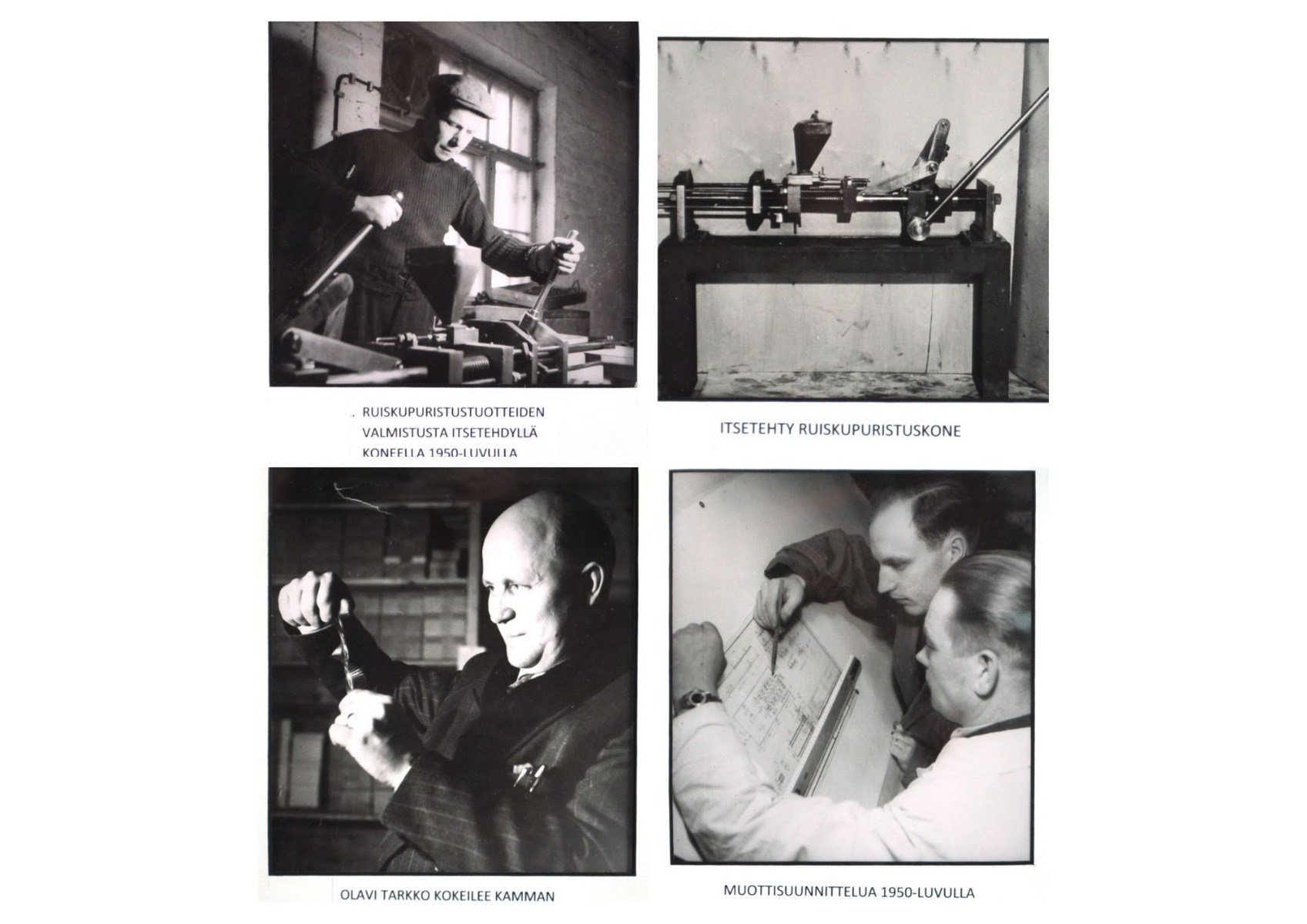

After the wars there was a shortage of machines and raw materials everywhere. Steel for molds and machinery was acquired for Plastex from scrap ships and military equipment, cannon parts, and all kinds of iron and metal scrap. Scrap was brought by train to Lohja station and hauled from there by horse to Plastex’s yard. From it came, among other things, the button and comb machines and their molds.

According to the annual report preserved from 1948, the greatest shortage concerned raw materials, which had to be obtained from abroad. Their import was regulated due to the ongoing currency shortage in the country. The most important raw materials in 1948 were cellulose acetate, polystyrene, and phenolic, urea, and melamine resins—i.e., thermosets. About 1,400 tons of raw materials were used.

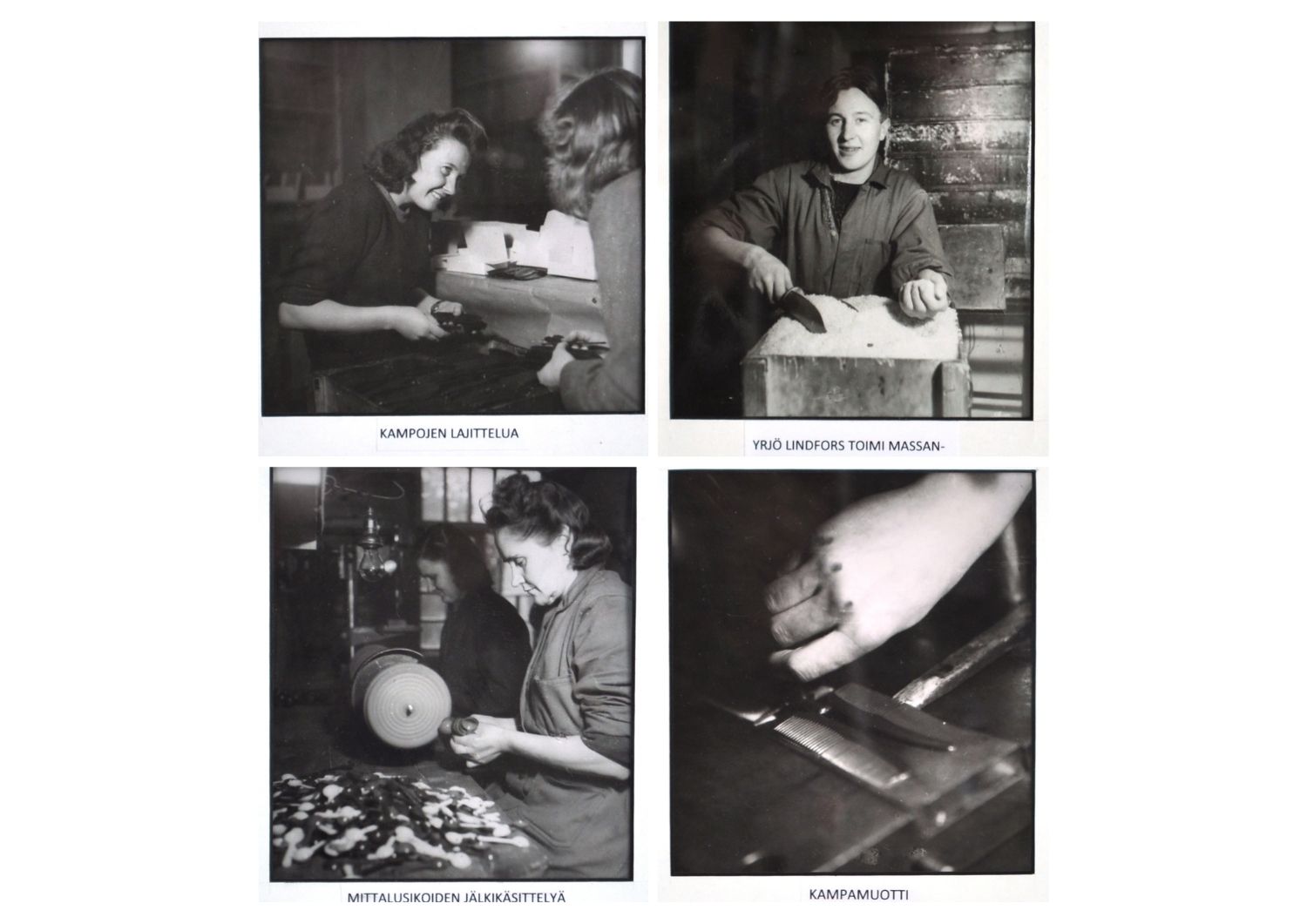

In 1948 Plastex’s principal product was the comb. With self‑made molds, fourteen different comb models were produced, totaling 234,673 dozen. A year later there were already 28 models.

Funnels and soap boxes were made from Bakelite, and industrial contract work included radio knobs, toothbrush handles, and, among other items, garter buckles and handbag buttons.

Veteran employee Paavo Sivenius had joined Plastex as early as 1945. He recalls the old Plastex and especially its Bakelite department: “There was no way to protect yourself from the dust; the heat was intense and the smell. When I came home, they said I smelled like a stable. Bakelite was terribly black and powdery; sweat and grime just flowed. Nowadays it’s clean, and the materials have changed completely.”

Martti Hermunen has memories of the comb machine: “There were two comb machines. Combs were made from a material similar to what’s used here now; if I remember right, it was called ‘celluloid.’ That, too, could be ground and reused. Demand for combs was so enormous that as soon as you managed to get them finished, they were gone. Then came small hand‑operated machines like flax breakers. On them we made all kinds of badges—May Day badges—buckles, buttons, thimbles, and other small knick‑knacks.”

Pentti Laiho remembers that in those years the tool department had two engraving machines and three engravers who, working in shifts, toiled to produce as many as 20 new small molds per month.

By 1948 there were already 47 employees, and over the year nearly 100,000 hours of work were done in three shifts.

According to the 1948 annual report, Plastex made a profit and paid dividends to its owners, and donated a significant sum—over two million Finnish marks—to the Helsinki University of Technology as a base fund “for studies and research to develop and promote the plastics field, especially its thermoplastic side.” The donation was about one‑fifth of the company’s entire annual payroll.

“Is Your Kitchen Plastexed Yet?”

The economic climate worsened in the early 1950s, and raw materials were still extremely difficult to obtain. As a result, the turnover of the entire plastics industry declined. Plastex’s turnover fell by 25% from the previous year.

At this point Olavi Tarkko decided to give up Plastex after leading and developing it for seven years. The new owners were the chemistry professor and head of the chemistry department at the State Technical Research Center, Olli Ant‑Wuorinen, with 26 percent of the shares; another 26% belonged to Aarne and Pauli Mutakallio, then owners of Lahti Rautateollisuus. A third equal portion was owned by engineer Harry Schumacher, who became the company’s managing director. The remaining shares were owned by two Swedish engineers.

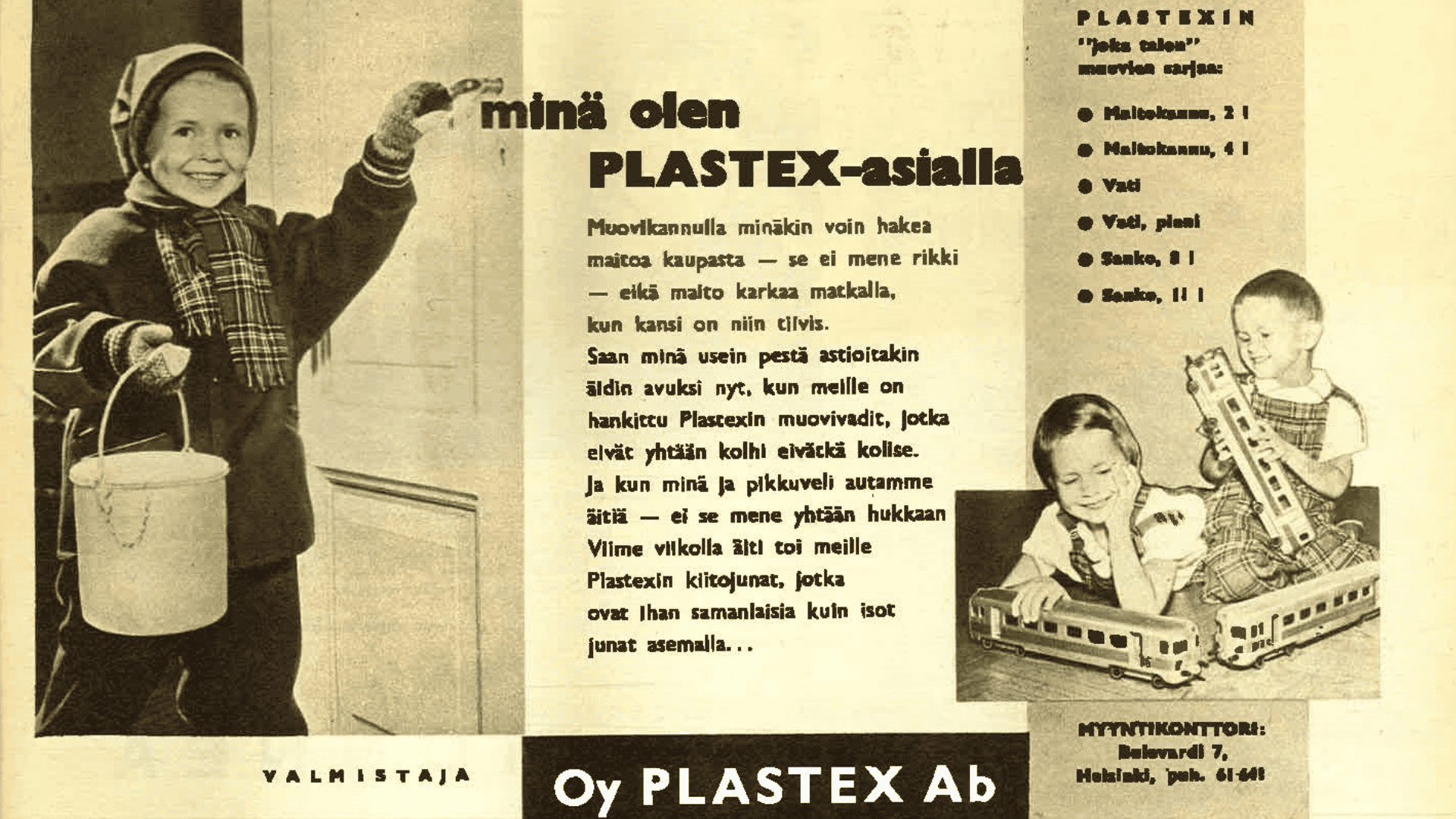

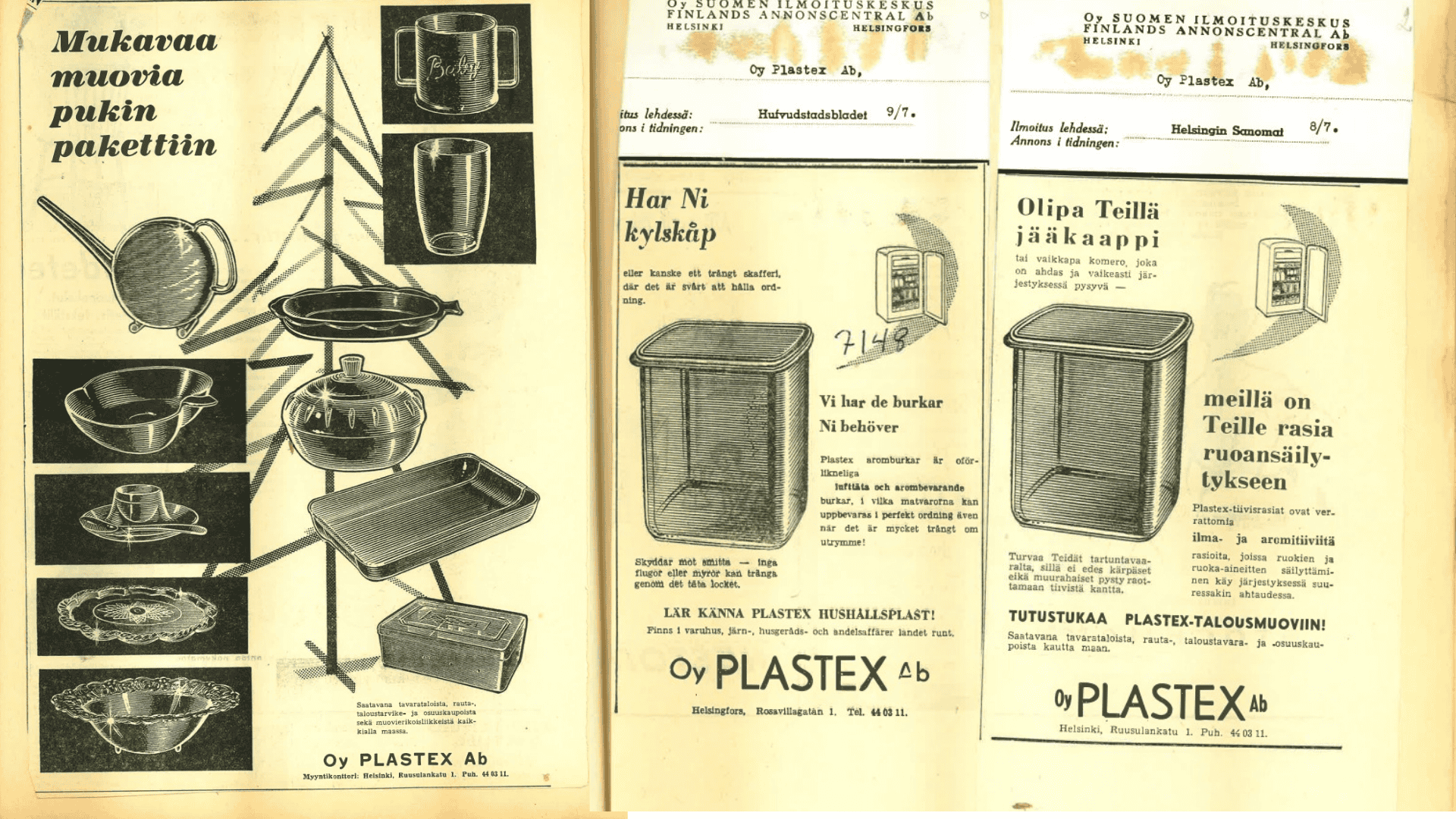

Construction of a new factory began immediately after the share transaction in 1953, and at the same time an unprecedented advertising campaign for plastic products was launched in Finland.

“Americanize your home too with Plastex ware. Speed, convenience, and practicality for the most important workshop in the house—the kitchen. America leads the way in kitchen inventions. Create your own convenient American kitchen…” Such lively ad copy was repeated in large advertisements in Helsingin Sanomat, Uusi Suomi, and Hufvudstadsbladet.

In issue 4/53 of Hopeapeili, a mother testifies in an advertisement: “Now my problem is solved. My kitchen has as good a system as my office desk. Everything within arm’s reach! That is the principle of Plastex household plastics.”

A Decade of Development

Sales hits in 1954 included a toy car, comb, washbasin, knife box, water jug, and children’s sunglasses. With new molds made in its own workshop, the company also produced, among other things, a schnapps glass, a doll’s head, and a flashing pistol—sold with Morse code as a bonus. Turnover rose by more than a third in 1954, and raw‑material consumption increased by more than half.

Alongside brisk advertising and an expanding product range, a new factory building rose on the slope near the Lohja station between 1954 and 1955, with dedicated departments for nearly every plastics manufacturing technique invented in Europe after the war. One reason for the number of lines was that at that time raw‑material licenses were granted separately for each line, and up to the 1960s the plastics industry suffered from raw‑material shortages. Negotiations with licensing authorities were so important that Plastex established a head office on Bulevardi in Helsinki to be close to them.

In the early 1950s most of Plastex’s machines were home‑built. They were developed and used to manufacture, among other things, plastic hose, nylon thread, fishing line, and—on a homemade machine—plastic film, reportedly the first in Finland. Production of these items was discontinued, however, when cheap foreign imports were liberalized in 1956–57.

Learning from Glassblowing

Pentti Laiho recalls how in the spring of ’52 Plastex blow‑molded the first plastic ball made by that method in Finland. “The staff went to the Karhula glassworks to watch glassblowing. The technique seen there was then applied to making plastic bottles. Later that same spring a blow‑molding machine was built, using a Reifenhäuser extruder. With it, three‑ to five‑liter plastic bottles were blow‑molded. The mold for the first bottle was made of oak.”

Finland’s largest injection‑molding machine arrived at Plastex in 1954. Success items produced on this American HPM machine included plastic buckets.

The Dutch Cipax patent made it possible to manufacture large plastic tanks with capacities up to 1,600 liters, and with the Danish Rotaflex patent, homes were adorned in the late 1950s with plastic lampshades and wastepaper baskets.

Plastex’s Crisis

When everything was being developed at once, the money ran out.

In 1960 the owners of Oy Plastex Ab were dissatisfied with the company’s results and decided to hire a new sales director. The position went to 32‑year‑old Erkki Ant‑Wuorinen. Four years earlier he had founded a retail and wholesale business in the plastics field. He knew Plastex’s products and believed in them.

Within two months sales grew briskly, but it also became clear that the company was in poor financial condition. During the managing director’s trip abroad, creditors were pressing the sales director: “There was nothing for it but to call an extraordinary general meeting and tell the owners about the financial crisis.”

Erkki Ant‑Wuorinen’s two‑month stint as sales director ended, and began his 25‑year journey as managing director of Oy Plastex.

Restructuring

The head office on Bulevardi in Helsinki was closed and moved to Lohja alongside the factory. Advertising was stopped. The number of employees was reduced from 150 to 70. Office staff were also reduced, leaving seven out of twenty‑five clerical employees. Of seven salespeople, one remained.

Accounting was thoroughly overhauled, and transactions began to be monitored daily. Erkki Ant‑Wuorinen says it seems inconceivable how companies in past decades could have operated without accurate monitoring.

“I get all the control figures from the factory and accounting every day. If I’m not on site, I receive them by telefax anywhere.”

Administrative director Elma Virto became Oy Plastex Ab’s chief accountant in 1963; at that time the 1960s restructuring and rationalization measures were in full swing.

“The office side was just being revamped. There were too many people here—too many bosses and subordinates. They were often painful cuts, but necessary. Thanks to them, the company began to recover. The first computer also came to the house—a semi‑automatic bookkeeping machine—which was initially viewed with suspicion. But computers then became invaluable tools. The machines have brought relief to routine work and increased the contribution to other tasks. They have sped up working and provided more accurate information more easily. We already have our third computer with display terminals,” Elma Virto says.

Focus on Blow Molding and Injection Molding

When Erkki Ant‑Wuorinen started at Plastex, the plant had 10 production lines. The manufacturing methods were film blowing, plastic hose, vacuum forming, Rotaflex, sintering, shrink tubing, bottle blow molding, and injection molding. As a result of rationalization, all other operations were discontinued, and focus was placed only on sintering, blow molding, and injection molding. The machinery of the blow‑molding and injection‑molding departments was renewed.

“It was necessary to try to predict which departments would have a future. I made clear which were our strongest sectors, and of course the best was blow‑molding plastic bottles, because in that field we were still alone in the market. We decided to choose blow‑molding as the main manufacturing method. It is closely connected to injection molding for producing caps and lids. We also make household plastics with the same method.”

The mold‑design and repair department also remained at Plastex, because machines need maintenance and repair, and the development of new products requires product design and mold making.

“Our production principle is that the company does not make anything that some Finnish factory already manufactures. If a product falls below profitability due to competition, its production is stopped immediately and new products are sought,” says Erkki Ant‑Wuorinen. On competition between companies he notes: “Finnish entrepreneurs should strive above all to compete with foreign companies.”

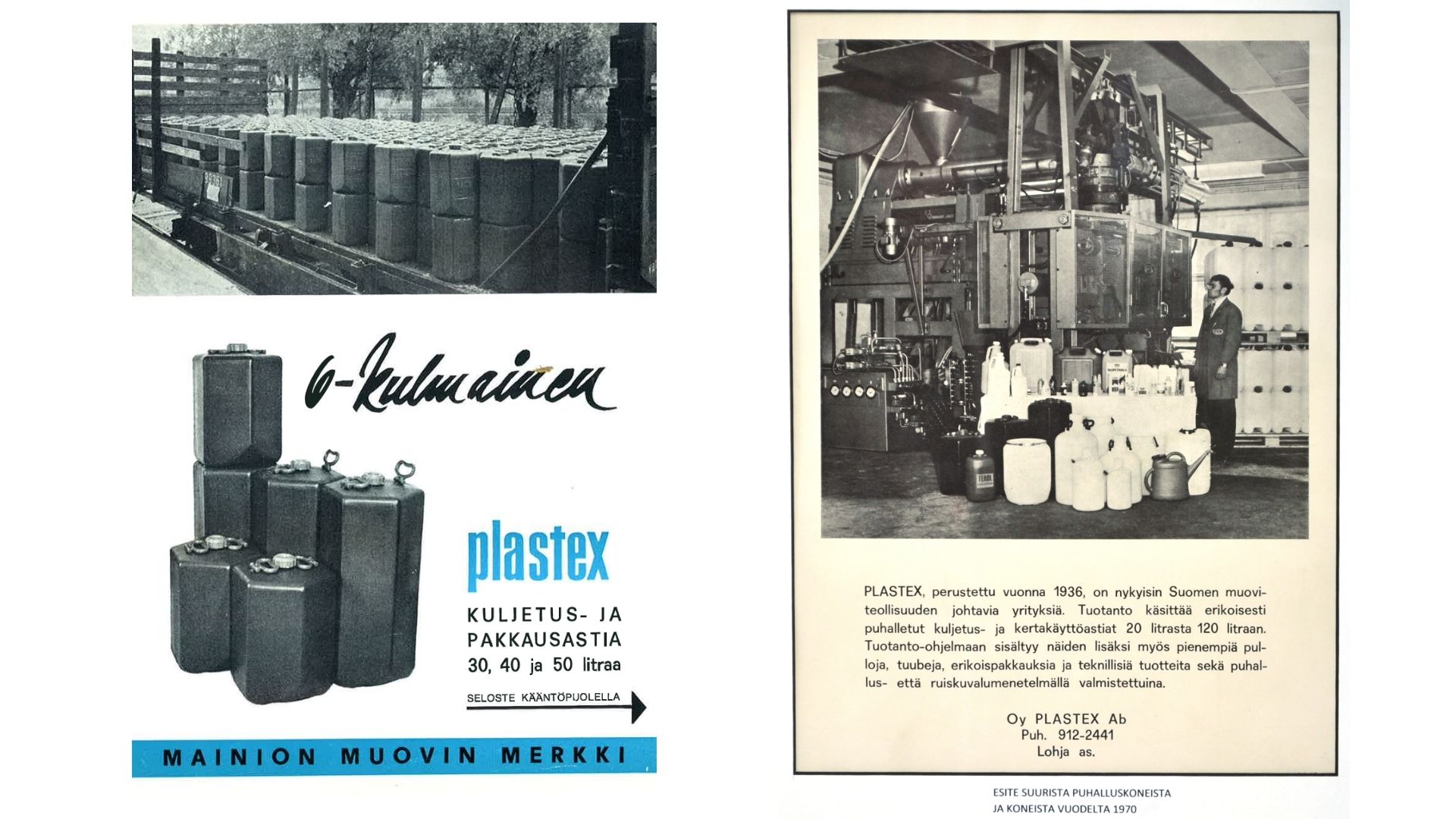

Mass Production of Blow‑Molded Products

On his first familiarization trip to European plastics industry, Erkki Ant‑Wuorinen went to a small workshop in Germany where a machine builder named Martin Rudolph manufactured large blow‑molding machines as one‑off pieces. A deal was struck on the spot. Erkki Ant‑Wuorinen says: “The Martin Rudolph blow‑molding machine proved to be an irreplaceable general‑purpose machine and paid for itself quickly. Among other things, Hankkija replaced all the glass demijohns it used for acid containers with our plastic vessels.”

Tests showed this hexagonal canister to be acid resistant, so the railway authorities recommended it. In 1962 it was awarded in packaging competitions as a high‑quality container for demanding transports.

In the 1960s, series production also included bottles of various sizes—up to 50‑liter transport containers—and watering cans, about which Kauppalehti reported on July 19, 1968. Plastex was said to have broken into the Swedish market: “Plastex won the Kooperativa Förbundet tender and received a large order—60,000 watering cans in total. Plastex’s selling points were the bold orange color and high quality.”

In the 1970s and 1980s Oy Plastex Ab continued to develop its production, renew its machinery, and expand its production lines. During this time, through active product development, the company established itself as one of the most significant manufacturers of plastic household goods in Finland—and increasingly abroad as well.

The most significant product groups in blow‑molded items have become various transport containers, especially for hazardous materials, and packaging for the technical‑chemical and food industries.

Present Day and the Future

Today, Plastex is a Finnish family‑owned company owned by the Ant‑Wuorinen family and led by Lauri and Arto Ant‑Wuorinen. The core of its expertise is in blow molding, and Plastex serves customers across Europe with a growing focus on exports. The mission is simple: we combine Nordic reliability with agile manufacturing so that products are safe and of high quality—every time.

Finnish

Finnish German

German France

France